| BUBBLES

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose

Any well read observer of financial history is likely to agree that little of the economic circumstances of the day are novel, and indeed it would be the fool who suggested that "this time it's different". It's my personal opinion that our present days of extreme financial markets valuations and the consequences of this over-pricing, were as predictable as they were by design. In the past year I have read two revealing books on the financial bubble in France and Holland and Great Britain following the death of Louis XIV by Professor Antonin Murphy of Trinity College, Dublin that I could not recommend more highly. They are (in the order in which I read them), John Law : Economic Theorist and Policymaker (Oxford University Press, 1997) and Richard Cantillon: Entrepreneur and Economist, (Oxford University Press, 1986). Both subjects of these works were politically influential and highly controversial financiers of the French regency period during the Mississippi and South Sea bubbles of 1720, and their intertwined lives are examined in detail by Professor Murphy. Economists and bankers of the time were developing and refining practices of central banking, government bond markets and stock exchange functions in order to promote economic growth in the wake of the burden of Louis XIV's debts. In addition to tendering a fascinating view into the upper echelons of the period, Professor Murphy quotes extensively from the correspondence and writings of Law and Cantillion to illustrate his understanding of the significance of these men not only to their day but how their views have determined the course of Western monetary architecture through to the present day. Professor Murphy states that Cantillon believed that "in a large state such a ‘national’ bank could do more harm than good: An abundance of fictitious and imaginary money causes the same disadvantages as an increase of real money in circulation, by raising the price of land and labour, or by making works and manufactures more expensive at the risk of subsequent loss. But this furtive abundance vanishes at the first gust of discredit and precipitates disorder. "The harm created by a central bank could be greatly magnified when a ‘Minister of State’ worked closely with the bank to force interest rates down via an expansionary monetary policy. He (Cantillon) understood how the minister could increase the issue of banknotes and use them to purchase government stock (ie govt bonds), causing the price of such stock to rise and the interest rate to fall. Expectations of further interest rate falls would cause the public to take up more of the stock, so amplifying the initial demand pressures for it: It is then undoubted that a bank with the complicity of a Minister is able to raise and support the price of public stock and to lower the rate of interest in the state at the pleasure of this Minister when the steps are taken discreetly, and thus pay off the state debt. "However, this type of operation was fraught with danger because of the self-interest of the people in power: But these refinements which open the door to making large fortunes are rarely carried out for the sole advantage of the state, and those who take part in them are generally corrupted. "The economy can survive this excessive expansion of the money supply as long as the excess money balances are kept within the financial circuit and used to purchase securities. But, once the excess money balances spill out of the financial circuit into the circular flow of real activity that Cantillon had detailed in Chapters 3 and 4 of BookII, then the whole system can blow up: The excess banknotes, made and issued on these occasions, do not upset the circulation, because being used for the buying and selling of stock they do not serve for household expenses and are not changed into silver. But if some panic or unforeseen crisis drove the holders to demand silver from the Bank the bomb would burst and it would be seen that these are dangerous operations." pp277-8, Richard Cantillon: Entrepreneur and Economist. Parallels to monetary policy today are obvious, the "abundance of fictitious and imaginary money" being created by central banks to ensure the liquidity of commercial banks is applied to speculation in derivatives, stock and bond markets, and residential and commercial real estate. Clearly, it is the intent of central bankers that this excess emission of money does not spill out into raising the price of labour and items of personal consumption and thereby avoiding disorder.

|

|

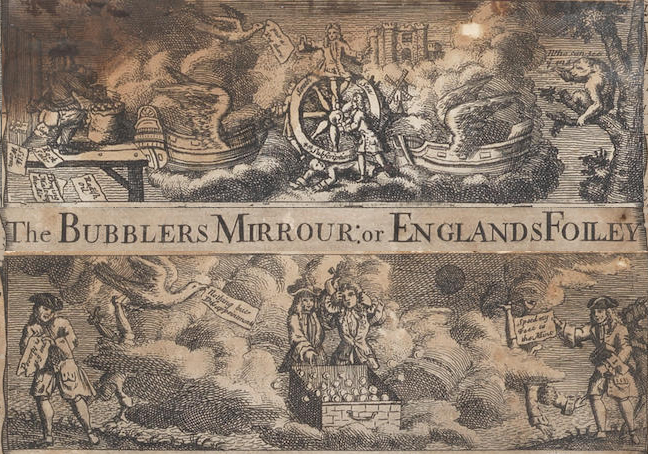

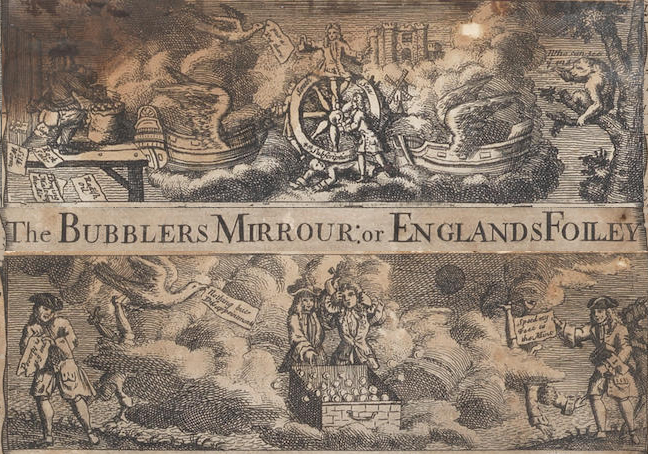

Two wonderful English eighteenth century copperplate engravings illustrating the impact of the South Sea Company bubble are shown here:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Full Size images may be viewed by clicking on each.

|

|